Goofy Crime Id Do It Again

Jennifer Pan's Revenge: The within story of a aureate child, the killers she hired, and the parents she wanted dead

Jennifer Pan'due south Revenge: The inside story of a gilt kid, the killers she hired, and the parents she wanted dead

Bich Ha and Huei Hann Pan were classic examples of the Canadian immigrant success story. Hann was raised and educated in Vietnam and moved to Canada as a political refugee in 1979. Bich (pronounced "Bick") came separately, as well a refugee. They married in Toronto and lived in Scarborough. They had 2 kids, Jennifer, in 1986, and Felix, iii years later, and institute jobs at the Aurora-based auto parts manufacturer Magna International, Hann as a tool and dice maker and Bich making machine parts. They lived frugally. Past 2004, Bich and Hann had saved enough to buy a large domicile with a two-automobile garage on a quiet residential street in Markham. He drove a Mercedes-Benz and she a Lexus ES 300, and they accumulated $200,000 in the bank.

Their expectation was that Jennifer and Felix would piece of work as hard as they had in establishing their lives in Canada. They'd laid the groundwork, and their kids would demand to improve upon information technology. They enrolled Jennifer in pianoforte classes at age four, and she showed early on hope. Past elementary school, she'd racked up a trophy case full of awards. They put her in figure skating, and she hoped to compete at the national level, with her sights assail the 2010 Winter Olympics in Vancouver until she tore a ligament in her knee. Some nights during elementary school, Jennifer would come home from skating exercise at 10 p.one thousand., do homework until midnight, so head to bed. The force per unit area was intense. She began cutting herself—little horizontal cuts on her forearms.

Equally graduation from Grade 8 loomed, Jennifer expected to be named valedictorian and to collect a handful of medals for her academic achievements. Only she received none, and she wasn't named valedictorian. She was stunned. What was the bespeak in trying if no one best-selling your efforts? And however, instead of expressing her devastation, she told anyone who asked that she was perfectly fine—something she chosen her "happy mask."

A close observer might have noticed that Jennifer seemed off, just I never did. I was a year behind her at Mary Ward Catholic Secondary in north Scarborough. Equally far equally Catholic schools become, it was something of an anomaly: it had the usual loftier academic standards and strict dress code, mixed with a incomparably bohemian vibe. It was easy to find your tribe. Brilliant kids and high-sounding misfits hung out together, across subjects, grades and social groups. If you played 3 instruments, took advanced classes, competed on the ski team and starred in the schoolhouse's annual International Nighttime—a showcase of various cultures around the world—you were absurd. Outsiders were embraced, geekiness celebrated (anime gild meetings were constantly packed) and precocious appetite supported (our almost famous alumnus, Craig Kielburger, pretty much ran his clemency, Free the Children, from the halls of Mary Ward).

It was the perfect community for a student like Jennifer. A social butterfly with an like shooting fish in a barrel, high-pitched express joy, she mixed with guys, girls, Asians, Caucasians, jocks, nerds, people deep into the arts. Exterior of school, Jennifer swam and practised the martial art of wushu.

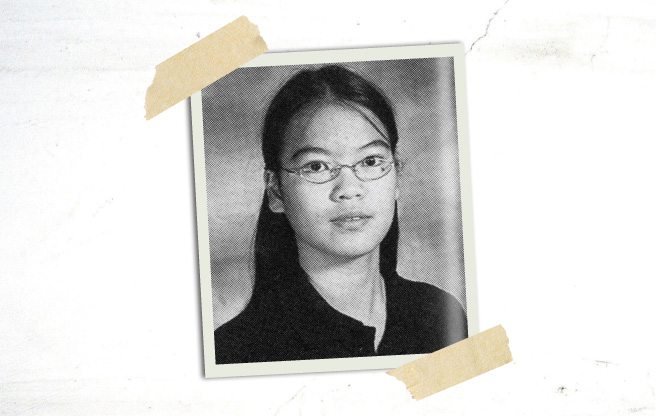

At five foot seven, she was taller than most of the other Asian girls at the school, and pretty but obviously. She rarely wore makeup; she had modest, circular wire-frame glasses that were neither fashionable nor expensive; and she kept her hair direct and unstyled.

Jennifer and I both played the flute, though she was in the senior stage ring and I was in junior. We would interact in the band room, had dozens of common acquaintances and were friends on Facebook. In conversation, she always seemed focused on the moment—if yous had her attention, you had it completely.

I discovered after that Jennifer's friendly, confident persona was a façade, beneath which she was tormented by feelings of inadequacy, self-doubt and shame. When she failed to win first place at skating competitions, she tried to hide her devastation from her parents, not wanting to add worry to their disappointment. Her female parent, Bich, noticed something was amiss and would condolement her daughter at nighttime, when Hann was asleep, proverb, "You know all we want from you is just your best—just do what you tin can."

She had been a top student in elementary school, but midway through Grade nine, she was averaging lxx per cent in all subjects with the exception of music, where she excelled. Using old written report cards, scissors, glue and a photocopier, she created a new, forged report card with straight Equally. Since universities didn't consider marks from Form 9 and 10 for admission, she told herself it wasn't a big deal.

Hann was the classic tiger dad, and Bich his reluctant cohort. They picked Jennifer up from school at the end of the twenty-four hours, monitored her extracurricular activities and forbade her from attending dances, which Hann considered unproductive. Parties were off limits and boyfriends verboten until later university. When Jennifer was permitted to attend a sleepover at a friend's house, Bich and Hann dropped her off late at nighttime and picked her up early the following morning. By age 22, she had never gone to a club, been drunk, visited a friend's cottage or gone on vacation without her family.

Presumably, their overprotectiveness was built-in of love and business organisation. To Jennifer and her friends, however, it was tyranny. "They were absolutely controlling," said ane quondam classmate, who asked not to be named. "They treated her like shit for such a long fourth dimension."

The more I learned well-nigh Jennifer'due south strict upbringing, the more I could relate to her. I grew up with immigrant parents who also came to Canada from Asia (in their example Hong Kong) with almost nothing, and a father who demanded a lot from me. My dad expected me to be at the meridian of my class, peculiarly in math and scientific discipline, to ever be obedient, and to be exemplary in every other way. He wanted a child who was like a trophy—something he could brag virtually. I suspected the achievements of his siblings and their children made him feel insecure, and he wanted my accomplishments to lucifer theirs. I felt like a hamster on a wheel, sprinting to meet some sort of expectation, solely adamant by him, that was always just out of achieve. Hugs were a rarity in my house, and birthday parties and gifts from Santa ceased around age 9. I was talented at math and figure skating, though my male parent well-nigh never complimented me, even when I excelled. He played downward my educational achievements, just like his parents had washed with him—the prevailing theory in our culture being that flattery spoils ambition.

Jennifer met Daniel Wong in Class 11. He was a yr older, goofy and gregarious, with a big laugh, a wide smile and a little paunch around his waistline. He played trumpet in the school ring and in a marching ring outside of school. Their relationship was platonic until a band trip to Europe in 2003. After a performance in a concert hall filled with smokers, Jennifer suffered an asthma attack. She started panicking, was led exterior to the tour bus and nigh blacked out. Daniel calmed her down, coaching her breathing. "He pretty much saved my life," she later said. "It meant everything." That summer, they started dating.

Of Jennifer'southward friends, I knew Daniel all-time. Nosotros met in my Grade ix yr at Mary Ward, and he would come over to my house nearly every mean solar day afterwards schoolhouse to watch TV and play Halo on my Xbox. He would often stick around and swallow dinner with my family. Dan spoke to my parents in Cantonese, and my dad would regularly buy him Zesty Cheese Doritos—his favourite. When Daniel was in his final year at Mary Ward, nosotros drifted apart, and midway through the year, he transferred to Primal Carter Academy, an arts school in North York. He was falling behind at Mary Ward, and, unbeknownst to me, he had been charged with trafficking after cops institute half a pound of weed in his car.

Jennifer's parents causeless their daughter was an A pupil; in truth, she earned generally Bs—respectable for almost kids but unacceptable in her strict household. Then Jennifer continued to doctor her report cards throughout high school. She received early acceptance to Ryerson, but then failed calculus in her terminal year and wasn't able to graduate. The academy withdrew its offer. Desperate to go along her parents from digging into her high school records, she lied and said she'd be starting at Ryerson in the fall. She said her program was to do two years of science, so transfer over to U of T's pharmacology program, which was her father's hope. Hann was delighted and bought her a laptop. Jennifer collected used biology and physics textbooks and bought school supplies. In September, she pretended to attend frosh week. When it came to tuition, she doctored papers stating she was receiving an OSAP loan and convinced her dad she'd won a $3,000 scholarship.

She would pack up her book pocketbook and accept public transit downtown. Her parents assumed she was headed to class. Instead, Jennifer would go to public libraries, where she would research on the Spider web what she figured were relevant scientific topics and make full her books with copious notes. She'd spend her free fourth dimension at cafés or visiting Daniel at York University, where he was taking classes. She picked up a few day shifts as a server at E Side Mario'due south in Markham, taught piano lessons and later tended bar at a Boston Pizza where Daniel worked every bit a kitchen manager. At habitation, Hann often asked Jennifer most her studies, but Bich told him not to interfere. "Let her be herself," she'd say.

In gild to keep the charade from unravelling, Jennifer lied to her friends, besides. She fifty-fifty amplified her dad's meddling ways, telling 1 friend, falsely, that her male parent had hired a private investigator to follow her.

After Jennifer had pretended to be enrolled at Ryerson for two years, Hann asked her if she was however planning to switch to U of T. She said yes, she'd been accustomed into the pharmacology programme. Her parents were thrilled. She suggested moving in with her friend Topaz downtown for iii nights a calendar week. Bich sympathized with Jennifer's long commute each day and convinced Hann that information technology was a skillful idea.

Jennifer never stayed with Topaz. Monday through Wednesday, she stayed with Daniel and his family at their habitation in Ajax, a large house on a repose, tree-lined street. Jennifer lied to Daniel's parents as well, telling them her parents were okay with the arrangement and brushing off their repeated requests to come across Hann and Bich over dim sum.

After two more years, it was theoretically time to graduate from U of T. Jennifer and Daniel hired someone they plant online to create a imitation transcript, full of Every bit. When it came to the ceremony, Jennifer told her parents that the extra-large class size meant in that location weren't enough seats—graduating students were immune only one guest each, and she didn't want one of her parents to feel left out, so she gave her ticket to a friend.

Jennifer adult a mental strategy to deal with her lies. "I tried looking at myself in the third person, and I didn't like who I saw," she later on said, "only rationalizations in my caput said I had to keep going—otherwise I would lose everything that ever meant annihilation to me."

Eventually, Jennifer'southward fictional academic career began to plummet. While supposedly studying at U of T, she had told her parents about an exciting new development: she was volunteering at the blood-testing lab at SickKids. The gig sometimes required late-nighttime shifts on Fridays and weekends. Perhaps, she suggested, she should spend more of the week at Topaz's. But Hann noticed something odd: Jennifer had no uniform or key card from SickKids. And then the next mean solar day, he insisted that they drop her off at the hospital. As soon as the car stopped, she sprinted inside, and Hann instructed Bich to follow her. Realizing she was being tailed by her mom, Jennifer hid in the waiting expanse of the ER for a few hours until they left. Early the next morning, they chosen Topaz, who groggily told the truth: Jennifer wasn't there. When Jennifer finally came abode, Hann confronted her. She confessed that she didn't volunteer at SickKids, had never been in U of T's pharmacology program and had indeed been staying at Daniel'southward—though she neglected to tell them that she'd never graduated high schoolhouse and that her time at Ryerson was besides complete fiction.

Bich wept. Hann was apoplectic. He told Jennifer to exit and never come dorsum, just Bich convinced him to let their girl stay. They took away her cellphone and laptop for two weeks, later on which she was merely permitted to apply them in her parents' presence and had to suffer surprise checks of her messages. They forbade her from seeing Daniel. They ordered her to quit all of her jobs except for teaching piano and began tracking the odometer on the car.

Jennifer was madly in dear with Daniel, and solitary, too. For two weeks, she was housebound, her mother by her side nearly constantly—though Bich told Jennifer where her dad had hidden her phone, so she could periodically cheque her messages. In February 2009, she wrote on her Facebook page: "Living in my house is like living under house arrest." She likewise posted a note: "No 1 person knows everything about me, and no two people put together knows everything about me…I like beingness a mystery." Over the spring and summer, she snuck calls with Daniel on her cellphone at night, whispering in the dark.

Eventually, she was immune some measure of freedom, and she enrolled in a calculus course to get her final high school credit. Still, in defiance of her parents' orders, she visited Daniel in between piano lessons. 1 night, she arranged her blankets to expect like she was asleep, so snuck out to Daniel's house. Simply she forgot that she had her mother's wallet. In the morning, Bich went into the room to get information technology and discovered Jennifer was gone. Bich and Hann ordered Jennifer to come domicile immediately. They demanded that she apply to college—she could still be a pharmacy lab technician or nurse—and told her that she had to cut off all contact with Daniel.

Jennifer resisted, but Daniel had grown weary of their secret romance. She was 24 and still sneaking around, terrified of her parents' tirades just not willing to leave dwelling house. He told her to figure out her life, and he broke off their relationship. Jennifer was heartbroken. Presently thereafter, she learned that Daniel was seeing a girl named Christine. In an try to win back his attention and discredit Christine, she concocted a bizarre tale. She told him a human had knocked on her door and flashed what looked like a police badge. When she opened the door, a group of men rushed in, overpowered her and gang-raped her in the foyer of her house. And so a few days subsequently, she said, she received a bullet in an envelope in her mailbox. Both instances, she alleged, were warnings from Christine to leave Daniel alone.

In the spring of 2010, Jennifer reconnected with Andrew Montemayor, a friend from elementary school. According to Jennifer'due south afterwards show in courtroom, he had boasted most robbing people at knifepoint in the park near his home (a merits he denies). When Jennifer told him about her torturous relationship with her dad, Montemayor confessed that he'd once considered killing his own father. The notion intrigued Jennifer, who began imagining how much ameliorate her life would be without her male parent around. Montemayor introduced Jennifer to his roommate, Ricardo Duncan, a goth kid with black boom polish. Over bubble tea in betwixt her piano lessons, co-ordinate to Jennifer, they hatched a plan for Duncan to murder her father in a parking lot at his work, a tool and dice company called Kobay Enstel, near Finch and McCowan. She says she gave Duncan $1,500, earnings from her piano classes, and they agreed to connect afterward past telephone to adapt the date and time of the hit. But Duncan stopped answering her calls, and by early July, Jennifer realized she had been ripped off. (Duncan says she called him in early July, hysterical, requesting that he come and kill her parents. He said he felt offended and said no, and that the only money she gave him was $200 for a night out, which he promptly returned.)

Co-ordinate to the police, it was at this point that Daniel and Jennifer, who were back in contact and exchanging daily flirty texts, devised an even more sinister plan: they'd rent a striking on Bich and Hann, collect the manor—Jennifer's portion totalling near $500,000—and alive together, unencumbered by her meddling parents. Daniel gave Jennifer a spare iPhone and SIM menu, and connected her with an acquaintance named Lenford Crawford, whom he called Homeboy. Jennifer asked what the going rate was for a contract killing. Crawford said it was $twenty,000, but for a friend of Daniel'south it could be done for $x,000. Jennifer was careful to use her iPhone for crime-related conversations and her Samsung phone for everything else. On Halloween dark, Crawford visited the Pans' neighbourhood—probably to sentry the site. Kids in costume streaming upwardly and down the street provided the perfect cover.

On the afternoon of November 2, the programme took an unexpected plow. Daniel texted Jennifer, saying that he felt as strongly well-nigh Christine as she did most him. Suddenly everything was thrown into question. She texted Daniel: "So y'all feel for her what I feel for you, then call it off with Homeboy." Daniel responded, "I thought you wanted this for y'all?" Jennifer replied to Daniel, "I do, but I have nowhere to get." Daniel wrote back: "Call it off with Homeboy? You lot said y'all wanted this with or without me." Jennifer: "I want it for me." The next day, Daniel texted, "I did everything and lined it all upwards for y'all." It seemed Daniel wanted out of the organisation. Only within hours, they'd reverted to their old ways, texting and flirting. Later that day, Crawford texted Jennifer, "I need the time of completion, think virtually it." Jennifer wrote back, "Today is a no go. Dinner plans out and so won't be home in time." Over the following calendar week, there was a flurry of text and phone conversations between Jennifer, Daniel and Crawford. On the morning of November eight, Crawford texted Jennifer: "After work ok will be game time."

That evening, Jennifer watched Gossip Daughter and Jon and Kate Plus Eight in her bedchamber while Hann read the Vietnamese news down the hall before heading to bed around eight:30 p.g. Bich was out line dancing with a friend and cousin. Felix, who was studying engineering at McMaster University, wasn't home. At approximately 9:thirty p.1000., Bich came abode from her line dancing form, changed into her pyjamas and soaked her feet in front of the Tv set on the main floor. At 9:35 p.1000., a man named David Mylvaganam, a friend of Crawford's, called Jennifer, and they spoke for nearly 2 minutes. Jennifer went downstairs to say proficient nighttime to Bich and, as Jennifer later admitted, unlock the front door (a statement she eventually retracted). At x:02 p.m., the light in the upstairs written report switched on—allegedly a signal to the intruders—and a minute later, it switched off. At 10:05 p.m., Mylvaganam chosen once again, and he and Jennifer spoke for 3 and a half minutes. Moments later on, Crawford, Mylvaganam and a third man named Eric Carty walked through the front door, all iii conveying guns. Ane pointed his gun at Bich while some other ran upstairs, shoved a gun at Hann'due south face and directed him out of bed, down the stairs and into the living room.

Upstairs, Carty confronted Jennifer outside her bedchamber door. According to Jennifer, Carty tied her arms backside her using a shoelace. He directed her back inside, where she handed over approximately $two,500 in cash, so to her parents' bedchamber, where he located $1,100 in U.S. funds in her mother's nightstand, and then finally to the kitchen to search for her mother's wallet.

"How could they enter the house?" Bich asked Hann in Cantonese. "I don't know, I was sleeping," Hann replied. "Close up! You lot talk too much!" one of the intruders yelled at Hann. "Where'southward the fucking coin?" Hann had just $60 in his wallet and said as much. "Liar!" one homo replied, and pistol-whipped him on the back of the head. Bich began weeping, pleading with the men non to hurt their daughter. One of the intruders replied, "Residuum bodacious, she is nice and will non be injure."

Carty led Jennifer back upstairs and tied her arms to the banister, while Mylvaganam and Crawford took Bich and Hann to the basement and covered their heads with blankets. They shot Hann twice, once in the shoulder then in the face. He crumpled to the floor. They shot Bich three times in the head, killing her instantly, then fled through the forepart door.

Jennifer somehow managed to reach her phone, tucked into the waistband of her pants, and dial 911 (despite, as she after claimed, having her hands tied behind her back). "Help me, delight! I need help!" she cried. "I don't know where my parents are! … Please hurry!" At the 34-second mark of the phone call, the unexpected happens: Hann tin can exist heard moaning in the groundwork. He had awoken, covered in blood, with his dead wife's body adjacent to him, and crawled upward the stairs to the master floor. Jennifer yelled down that she was calling 911. Hann stumbled outside, screaming wildly, and encountered his startled neighbour, who was most to leave for work, in the driveway side by side door. The neighbour called 911. Constabulary and an ambulance arrived at the scene minutes later, and Hann was rushed to a nearby infirmary, then airlifted to Sunnybrook.

York Regional Police interviewed Jennifer just before three a.m. She told them that the men had entered the firm looking for money, tied her to the banister, and taken her parents to the basement and shot them. Two days afterward, the police brought her in again to give a second statement. At their request, she showed how she contorted her torso to get her telephone—a flip phone—out of her waistband to place a call while tied to a banister.

Holes began to emerge in Jennifer's story. For example, the keys to Hann's Lexus were in plain view past the front door. If it were indeed a dwelling invasion, why did the intruders not have the car? And why didn't they have a crowbar to go in, or a backpack to carry the loot, or zip ties to restrain the residents? And most important: why would they shoot 2 witnesses but leave one unharmed? The police assigned a surveillance team to monitor Jennifer'southward movements.

By November 12, Hann had woken upwards from his 3-day induced coma. He had a broken os nearly his eye, bullet fragments lodged in his confront that doctors couldn't remove and a shattered cervix bone—the bullet had grazed the carotid artery. Remarkably, he remembered everything, including two troubling details: he recalled seeing his daughter chatting softly—"like a friend," he said—with one of the intruders, and that her arms were not tied behind her back while she was being led around the house.

On November 22, the police brought Jennifer in for a third interview. This one developed a different tone: the detective, William Goetz, said that he knew she was involved in the law-breaking. He knew that she had lied to him, and said it was in her best interest to fess up. Jennifer, hunched over and sobbing, asked repeatedly, "But what happens to me?"

Over nearly four hours, Jennifer spun out an absurd caption. She said the attack had been an elaborate plan to commit suicide gone horribly wrong. She had given upwards on life but couldn't manage to kill herself, then she hired Homeboy, whose real name she claimed not to know, to practise it for her. In September, yet, her relationship with her father had all of a sudden improved, and she decided to call off the hit. But somehow wires got crossed, and the men ended up killing her parents instead of her. Police arrested Jennifer on the spot. In the bound of 2011, relying on analysis of cellphone calls and texts, they nabbed Daniel, Mylvaganam, Carty and Crawford, and charged all five with first-degree murder, attempted murder and conspiracy to commit murder.

The trial began on March 19, 2014, in Newmarket. It was expected to terminal half-dozen months but stretched for nearly ten. More than than l witnesses testified and more than 200 exhibits were filed. Jennifer was on the stand for seven days, bobbing and weaving in a futile effort to explicate away the damning text messages with Crawford and Daniel and the calls with Mylvaganam, and desperately trying to convince the jury that while she had indeed ordered a hit on her begetter in August 2010, three months later on she had wanted nothing of the sort.

Before the jury delivered the verdict, Jennifer appeared nearly upbeat, playfully picking lint off her lawyer'southward robes. When the guilty verdict was delivered, she showed no emotion, only one time the press had left the courtroom, she wept, shaking uncontrollably. For the charge of showtime-degree murder, Jennifer received an automatic life sentence with no chance of parole for 25 years; for the attempted murder of her father, she received another sentence of life, to be served concurrently. Daniel, Mylvaganam and Crawford each received the aforementioned judgement. Carty's lawyer fell ill during the trial, and his trial was postponed to early 2016. The gauge granted two not-communication orders, i banning communication among the v defendants until Carty'south trial is complete, and a second between Jennifer and her family, at the latter's asking, effectively preventing Jennifer from speaking to her begetter or brother e'er over again. Her lawyer addressed the order in courtroom. "Jennifer is open to communicating with her family if they wanted to," he said.

Hann and Felix both wrote victim affect statements. "When I lost my married woman, I lost my girl at the same fourth dimension," Hann wrote. "I don't experience similar I have a family anymore. […] Some say I should experience lucky to be alive but I experience like I am dead too." He is now unable to work due to his injuries. He suffers anxiety attacks, insomnia and, when he tin slumber, nightmares. He is in constant pain and has given up gardening, working on his cars and listening to music, since none of those activities bring him joy anymore. He can't conduct to be in his house, so he lives with relatives nearby. Felix moved to the Due east Coast to find piece of work with a private engineering company and escape the stigma of beingness a member of the Pan family. He suffers from depression and has become closed off. Hann is drastic to sell the family abode, but no i will purchase it. At the cease of his statement, Hann addressed Jennifer. "I hope my daughter Jennifer thinks almost what has happened to her family and can go a good honest person someday."

This was a difficult story for me to write. It's complicated to report on a murder when you were once friends with the people involved. Late concluding yr, I drove up to the correctional facility in Lindsay a few times to meet Daniel. In the harsh, white, empty halls of the massive building, fifty-fifty separated from me by a large pane of Plexiglas, he still seemed so familiar—a niggling pudgy, happy, cracking jokes. His favourite colour was always orange, merely he tugged on his vivid pumpkin jumpsuit and said he'd cooled on the color lately, so bankrupt into a big laugh. He asked how I was doing, and I told him my parents had recently separated, and how information technology had been tough on me. He said that if he ever got out, he would requite my dad relationship communication. I asked him if he ever wonders whether, if even niggling things had gone merely slightly differently, he wouldn't exist in prison house. He shook his head and said thinking like that could drive a person mad. He said the all-time affair for him was to focus on reality: that he was in jail, and he had to brand the all-time of it. Daniel said he'd bonded with the Cantonese speakers in his block and was helping them conform to life within. When I asked him almost the case, he clammed upwards, citing limitations prepare past his lawyer. He intends to appeal, as practice Jennifer, Mylvaganam and Crawford. Presuming they lose, they'll be eligible for parole in 2035. Jennifer will exist 49, Daniel 50.

A number of questions linger. Was Jennifer mentally ill? A chemical imbalance would certainly brand the ordeal easier to empathize. But her lawyers didn't effort to present her as unfit to stand trial. That leaves a harder conclusion: that Jennifer was in consummate control of her faculties. That she wanted Bich and Hann expressionless and put a plan into action to get in happen. That the guilt of years of her snowballing lies and the shame when information technology all came out drove her to murder.

Information technology'due south not that simple, though. I believe that on some level, Jennifer loved her parents. "I needed my family to exist around me. I wanted them to accept me; I didn't desire to live lone […] I didn't want them to abandon me either," she said on the stand up. She was hysterical on the phone when she chosen 911 and teared upward in the courthouse while describing the sound of her parents existence shot. Nonetheless how practice you believe a liar? Jennifer lied in all iii statements she gave to police. Under oath, she was repeatedly caught in tiny half-truths.

Some recall her parents were to arraign. "I think they pushed her to that point," a friend of Jennifer'southward told me. "I honestly don't call up Jennifer is evil. This is merely two people she hated." In February, I submitted divide formal requests to interview Jennifer and Daniel. They declined. The result is the purgatory of not knowing what my onetime schoolmates were thinking, feeling and hoping for. And it'southward probable I never will.

Source: https://torontolife.com/city/jennifer-pan-revenge/

0 Response to "Goofy Crime Id Do It Again"

Post a Comment